What Bialiatski Told About Prison, War, the Nobel Prize, and the Future of Belarus. Full Text of the Interview

Ales Bialiatski, the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, released from prison and transported to Lithuania, gave a major interview to Radio Svaboda in Vilnius. The full text of this interview has been published.

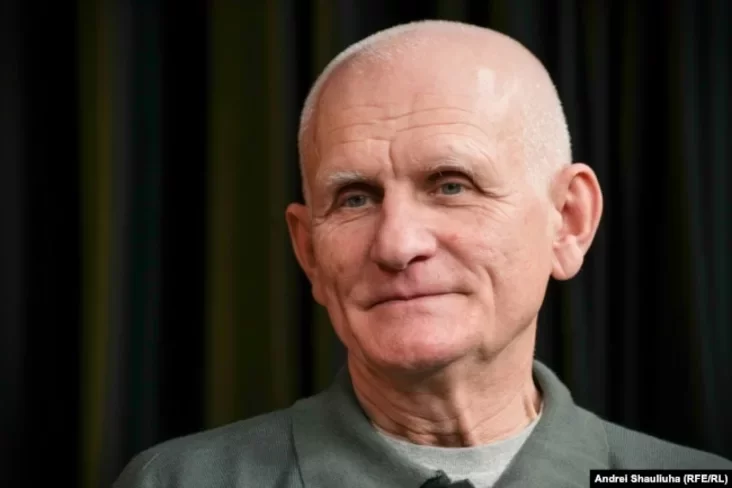

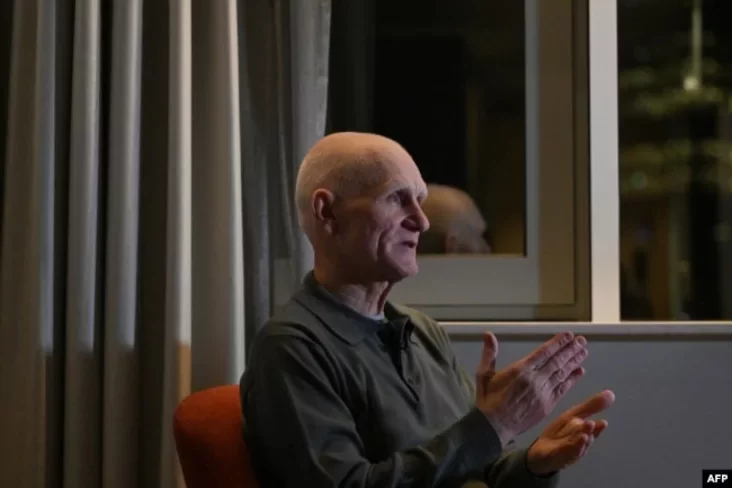

Ales Bialiatski, the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, in an interview for the Belarusian service of Radio Svaboda three days after his release from prison. Vilnius, December 16, 2025

— We want to talk with you, Ales, as a human rights defender in prison, a Nobel laureate in prison: what you saw, what you personally experienced, in what you participated, in whose fate, and what conclusions you drew from it, how you saw Belarus from behind bars. And first of all, I would like to ask why in 2021 you decided to stay in Belarus, understanding what it was like the previous time you were arrested, understanding the scale of the repressions that had already unfolded by that time. And did you discuss this with your colleagues Stefanovich and Labkovich?

— Indeed, we were in the thick of the events of 2020 and 2021, though not in the front rows, but as far as assisting the repressed, gathering information, disseminating information – "Viasna" did everything to collect information about people who were then massively beaten and imprisoned, who disappeared without a trace, and about their fates. We sought opportunities for assistance. And at first, when the authorities' strike hit broad circles of activists, political activists, they somehow didn't notice us: it was clear that the KGB and the police simply didn't have enough resources for everyone. But in 2021, as they gradually expanded the scope of repressions, it became clear that we too were under close scrutiny.

Radio Svaboda journalist Valer Kalinouski and Ales Bialiatski. Vilnius, December 16, 2025

In September 2020, Marfa Rabkova, a member of "Viasna," was arrested. In January 2021, the first searches took place at the homes of our "Viasna" friends and at the "Viasna" offices. And after that, it became clear that repressions directly and personally against those who had worked at "Viasna" for a very long time, who were well-known, who gave interviews, who worked in various areas of human rights activity in Belarus, might soon follow. My colleagues were traveling abroad for a conference at that time, and when they returned to Belarus in July 2021, they were stopped at the border; there was a very detailed search. This was another alarming call, after which we met with Uladz Labkovich and Valiantsin Stefanovich. Let me remind you, this was during COVID. I remember it as if it were now, how we sat in different corners of the room and talked about our future plans, about what might happen. And I said then that as the head of an organization that was already suffering from repressions – and our volunteers and Marfa Rabkova were already in prison then – it was not appropriate for me to flee into emigration, to leave, to depart from Belarus, because it wouldn't look quite right. Especially since the prominence of our organization, "Viasna," was certainly noted by both the Belarusian authorities and the international community. We had to withstand this blow and be together with the victims of political repressions, in general, with the broad circle of people who continued the resistance; we had to help, we helped in Belarus until the last minute, remaining there, those who were already imprisoned. This was assistance of the most diverse kind: transfers to prisons, moral support for families, information gathering, presence at trials, monitoring of these political trials. We did this work; the question of whether to leave, we discussed and decided – no, we stay. And literally a couple of days after this discussion, arrests took place; we and a number of our "Viasna" friends were detained. There were mass searches, over 120 searches across Belarus in total, related to "Viasna." These included regional "Viasna" offices, Minsk offices, and our apartments, which the police broke into – operatives conducted these searches; it was very large-scale, widespread. The three of us remained in the Valadarka pre-trial detention center – Uladz Labkovich, Valiantsin Stefanovich, and I. For some time, Uladz Labkovich's wife was also there, but after 10 days, thank God, she was released, and the three of us remained in this situation, along with hundreds of other political prisoners who were in Belarus at that time.

Ales Bialiatski in an interview for the Belarusian service of Radio Svaboda three days after his release from prison. Vilnius, December 16, 2025

Morally, I was ready; it was déjà vu for me, as if I had returned, rewinding 8 years, to the time when I was held in Valadarka. In 2021, I found myself there again, only in neighboring "cells," in neighboring chambers. There was a feeling that everything here was familiar, that the machine had turned some part of life, and you had returned to these not quite, I would say, normal conditions. Because it's always overcrowded there, always problems with medicine, all sorts of other problems. I returned to this difficult situation. We stayed; it's another matter that, perhaps, we didn't expect, didn't calculate that our imprisonment would be so long. From the moment of detention to the moment of my and Uladz Labkovich's release, which occurred on December 13, 2025, 4 years and 5 months passed, nearly 4 and a half years. And Valiantsin Stefanovich continues to sit to this day; his prison counter, the timer, hasn't stopped, it continues to tick day after day, the imprisonment continues. What influenced such a long, prolonged imprisonment – our sentences were quite long: I was given 10 years of imprisonment, Valiantsin – 9, Uladz – 7 years? Undoubtedly, the situation with the war in Ukraine influenced it, which suddenly pushed the very theme and problems of Belarus into the background, and the fact that we practically began to have a state of war. Belarus was very strongly drawn into this military campaign; there's no need to say how much Russian military equipment passed through Belarus. The entire war, in general, began from Belarus: Russian troops entered Ukraine from Belarusian territory. And, of course, it's a tragedy that our stay in prison is, to some extent, devalued; we became hostages, we became, in a broad sense, one could say, prisoners, which we effectively were until the last day of imprisonment, until our release.

— Ales, we will return to these painful topics – the topic of war and the topic of your detention in prison – but now I would like to return to that meeting of the three of you, still free, in different corners of one room. Does that mean you developed a kind of "plan B" in case of the arrest of the entire "Viasna" leadership?

— Gradually, our friends, other members of the organization, after Marfa's arrest and after the first searches in January 2021, effectively left Belarus. We organized this departure of our friends. Valiantsin Stefanovich said so at the trial in his final speech: we are ready to sit in prison, because "Viasna" itself, our younger generation, which has grown over the 25 years of "Viasna"'s existence (by the way, next year will be 30 years), has moved abroad, and "Viasna" will continue to live and work, despite the fact that we, the founders of "Viasna," who worked there for 20 years, are in captivity.

— We saw how productively "Viasna" works, how it does incredible things, and were you aware of this there?

— I was in Vilnius once after "Viasna" left Belarus, despite COVID. We didn't just plan an evacuation for people to leave, sit there, and wait for the situation to change, but so that they, having left, would immediately connect to work and continue effectively all the directions that the "Viasna" human rights center is engaged in. Therefore, the work did not stop; it was immediately continued. I managed to visit here, in Vilnius, at the beginning of 2021, when the first "Viasna" office was opened here and its work, thank God, began. I returned to Minsk. Their separate life from us had already begun for several months. Although it must be said that when human rights defenders are in prison, the situation is paradoxical — there you don't engage in human rights defense, because you don't have such opportunities. But the very fact of a human rights defender being in prison is effectively a continuation of our work, our activity, just in a different form.

Books from the "Svaboda Library." "Bialiatski's Case" and "Voices of Belarus — 2022"

Our friends abroad worked in our traditional directions. And we sat and by our sitting testified – that in Belarus, the level of democracy is zero or negative, as is the level of human rights observance, and the authorities' attitude towards civil society. Because the imprisonment of a human rights defender in any country is the very first marker that shows what is happening with human rights in that country. The same applies to Belarus. The imprisonment of human rights defenders and journalists vividly demonstrates that mass repressions are taking place in the country, democracy is absent, human rights are absent. The country is in a critical, abnormal state. We went through all this 100 years ago. The most interesting thing is that history has come full circle. In the 1920s-30s, mass repressions took place in Belarus against the Belarusian intelligentsia, against youth activists, against writers, historians, cultural figures – in general, against those people who created an independent Belarus but were not communists in their convictions. They were all imprisoned, repressed. And this circle has turned. Some conditions of detention are difficult to compare with that time. After all, 100 years have passed. But nevertheless, they cannot be called normal. We practically experienced everything that Solzhenitsyn described in "The First Circle." And we experienced our circles there – together with other political prisoners. This means that we all went through storms. Uladz Labkovich has now been released from a closed prison. We were with other political prisoners who effectively represent all of Belarusian society. Everyone sits there. Students, youth, teachers, doctors, and athletes – who isn't there? And military personnel, everyone sits there. Human rights defenders sat there and continue to sit there. Currently, Marfa Rabkova and Valiantsin Stefanovich are in prison, let me remind you – Nasta Loika and other volunteers, people who worked in human rights organizations, provided assistance. This shows that we are part of our active Belarusian society; we have experienced the same problems, the same tragedy that has unfolded in Belarus in recent years. And we are not ashamed; you cannot say that we hid, stayed out of these events during this time.

— It's natural for a human rights defender in Belarus to be in prison; you wrote this to me from your previous imprisonment in the Babruisk colony. Now, correspondence could not be established. Did you not have the thought, regret, that you would be more effective free?

— I repeat what Valiantsin Stefanovich said: our job, in short, was to sit. And the job of other human rights defenders from our organization was to work. We all did a common cause; that's how it turned out. And one must also understand that after the moment of arrest, you have no choice. You cannot choose whether you would stay in Belarus or leave; you're already in, you've gone. This machine has begun to grind you, your bones, as it were; it has drawn you in, you are in this unhurried but merciless circle that spins you, and little depends on your desires anymore. The only thing that is very important there is to preserve yourself, to preserve your principles, and if possible, to preserve your health. These were the daily questions for us, and we dealt with them there, beyond the mission of human rights defenders, the high mission I spoke about.

Ales Bialiatski met his wife after his release, Vilnius, December 14, 2025

Of course, I didn't think every day, nor did my colleagues, that we were such good fellows for sitting in prison with other inmates. We didn't think about that; we thought about the most basic things: how to organize our lives so that they would be more or less decent under the most diverse and difficult conditions. As a friend of mine said: I slept on concrete for four years there. Figuratively speaking, this is a metaphor – sleeping on concrete throughout imprisonment; it forced us primarily to think about some current matters of elementary survival, but at the same time, about endurance. We had to endure this situation, not give in, not succumb to illusions, because as for writing appeals for pardon, attempts to establish contact with the administration, writing letters to the authorities of Belarus – all of this did not concern us. We were beyond all these waverings; we firmly held our position, on the one hand, and on the other hand – we sat quietly.

— But let's move from 2021 to 2022. There was a very important event at the end of that year, when the war had already begun. You were awarded the Nobel Prize, and Natallia Pinchuk, your wife, delivered the Nobel speech in Oslo. There were many publications, a lot of interest. This is truly a historical event for Belarus – the second Nobel Prize, the first Nobel Peace Prize, and a prize to a political prisoner, a human rights defender. How did you find out about it? What was the reaction of your cellmates to this event, to this speech, and the reaction of the administration, which is especially interesting?

— The news was unexpected for me, although there was a discussion about who would be the Nobel laureate. At that time, it was possible to subscribe to the Russian "Nezavisimaya Gazeta," which also provided materials about Belarus, still quite sharp (I don't know, maybe it's no longer there, it's not published). And one could subscribe to it, given that all independent Belarusian media outlets were closed. It was the only source from which one could get some current information about what was happening in Belarus. The most interesting thing – from a newspaper published in Moscow. And there, on the eve of the Nobel laureate announcement, there was an article about it and about Belarusians being on the list, but I wasn't mentioned there. And I was absolutely calm, because I knew that receiving a Nobel Prize is actually not that simple. There are many factors that must align for it to be received.

Ales Bialiatski near the US Embassy in Vilnius after his release from prison in Belarus and transport to Lithuania. December 13, 2025

Therefore, there were no thoughts at all that I could be on that list and become a laureate. And I learned about this news in October, when it was officially announced and when the media outlets somewhere behind the walls of "Valadarka" widely wrote about it. I was then taken to familiarize myself with the materials of the criminal case. The case had 210 volumes. Such a multi-kilogram case: imagine, 210 folders of these papers in our case. These are thousands of documents that had to be reviewed before the court session. And standing in the corridor before going into the room to read these volumes, where usually a lawyer and one of the investigators leading the case were also sitting, I hear one of the prisoners tell me (there were quite a lot of political prisoners there, I didn't know this guy): "Ales, it seems you are a Nobel laureate?" It seems… I first took it as a joke, didn't believe it at all, but when I went in and the lawyer confirmed what she had read, what other lawyers had told her, that "your defendant is a Nobel laureate," then it was a huge impression for me. I was deeply impressed because I was absolutely not ready; if there was one thing I wasn't thinking about then, it was the Nobel Prize. Well, and one also needs to understand, I immediately realized this, that it wasn't purely my prize; it wasn't given *to me*. As, by the way, these prizes are often given – symbolically, to emphasize some phenomenon, some problem that exists in the world or in a particular society. This is how it was given in its time to Andrei Sakharov 50 years ago, to emphasize the absence of human rights in the Soviet Union and to support the desperate work of human rights defenders of that Soviet era, because back then, human rights activity unequivocally ended in imprisonment, persecution.

Representatives of the Nobel Peace Prize laureates Jan Rachinsky (Russian organization "Memorial"), Natallia Pinchuk (wife of Ales Bialiatski), Oleksandra Matviichuk (Ukrainian "Center for Civil Liberties") in Oslo, December 10, 2022

This was a prize, let's say, to all democratically minded Belarusians who came out in 2020, came out in 2021, continued their struggle for democracy, for human rights, for a just society, for fair elections. This prize was given to all these people to emphasize the courageous act, effectively a feat, this popular surge that we saw with our own eyes, in which we participated as much as we could. It's clear that only we, "Viasna" or public organizations, could not have organized this. Millions of people who demanded freedom – this was the voice of democratic Belarus, of the people's Belarus. And the prize highlighted the problem of the suppression of freedom in Belarus, that the mass repressions against civil activists, which unfolded from 2020 and continued into 2021, must end; this is abnormal. These people were striving for the most basic, ordinary things. And the authorities, accordingly, are illegitimate; they violate human rights; this is effectively a junta that holds power illegally. This prize spoke of all this. I was only a representative, nothing more, one of those thousands, hundreds of thousands of people who wanted democracy and human rights in Belarus. I understood this perfectly, so I had no feeling then, and have none now, that this was some great merit of mine.

Ales Bialiatski immediately after his release and relocation from Belarus to Vilnius. December 13, 2025

I believe this is truly a national Belarusian prize; it belongs to all Belarusians, all democratic Belarusians who fought for democracy, who did and do what they can. This is undoubtedly an important point. And it must also be taken into account that along with me, two human rights organizations became laureates – a Russian one and a Ukrainian one. This emphasized the tragic, dramatic situation connected with the war that unfolded in the same year 2022; the prize drew attention to this military conflict because it is a peace prize. It sent a signal to both the Russian authorities, the Belarusian regime, and the Russian regime: stop the war, you are committing crimes. But the Belarusian and Russian authorities perceive this signal very uniquely. They only understand the politics of force, signals of strength, violence, like all dictators. They consider persuasion or humanitarian messages to be very unserious. And there is, in a certain sense, an underestimation of the significance of this prize; a lack of seriousness was present even during my further stay in prison.

— Ales, tell me, did your authority among prisoners and administration representatives grow after the Nobel Peace Prize?

— As for the prisoners, yes. Those who understand, who have ever heard about this Nobel Prize, who know something about it, they certainly treated me with respect. Especially now, when there was a lot of talk about whether Donald Trump would receive this prize or not in 2025, this again attracted attention. We sit in the so-called "lenka," in the "Lenin room," watching TV, and there are debates about whether Trump will receive the Nobel Peace Prize or not, and here sits a Nobel laureate among such... Twenty people sit on these benches, and he sits among them. Of course, for people, this was a kind of nonsense – how could such a thing be.

Ales Bialiatski. Vilnius, December 16, 2025

But considering that Belarusians are an unemotional people, and that this manifests even more in prison, because any emotions are suppressed by the administration, it is believed that you should sit there with your mouth shut, then, of course, there were fewer of these expressions and messages from the prisoners. But it was clear that even among criminals, among people who had never engaged in politics, who are generally negative about all politics, the news evoked a certain respect: this uncle is really very famous. This was consistently the case in both the colony and the pre-trial detention center. And as for the administration – I also noticed this – they know about it, first of all, but they are working. Especially those who are careerists. As in any strict state structure, there are more careerists, and there are, as it were, ordinary employees. And these careerists worked strictly according to instructions on how to treat political prisoners; all of this extended to me as well.

— So there was no leniency for the Nobel laureate?

— No, this was especially true for 2023, as soon as I arrived at the colony, and it was still the case in 2024. I went through everything that political prisoners went through. This included insults, and being addressed informally ("ty"), you were treated like an ordinary prisoner, like a political prisoner. If the regime head wanted to – he stripped you naked, made you squat, because he was conducting a full check, even though you only had a meeting with your lawyer. Before that, he stripped you, lest you smuggle in some note, or whatever he was looking for, I don't know. All of this – abuse and inhumane treatment – was, of course, present. And there were endless reports of violations of internal regulations; they loved issuing these papers. For any trifle, both justified and unjustified – that you weren't shaved, your shoes weren't cleaned, you cleaned your section poorly when it was your turn, you didn't greet a passing superior. All of this happened, and I myself didn't know that there were so many papers on me. But a couple of months ago, I reached half of my sentence. Considering the rule "one day in pre-trial detention counts as one and a half in a colony" and the fact that we spent almost two years in pre-trial detention, my pure sentence came out to 9 years and one and a half months – what I had to serve. Recently, I underwent an evaluation for half of this term and heard that, apparently, over two and a half years in the Horki colony, 23 reports of internal regulation violations were filed against me. I was considered a malicious violator. A Nobel laureate – a malicious violator of regulations. This is completely normal, without any schizophrenia for the local Horki administration.

Ales Bialiatski, the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, accompanied by his wife Natallia Pinchuk, tries on a new suit at a shopping center in Vilnius, December 14, 2025, the day after his release from prison

It was especially painful upon my release on December 13, when the deputy head of the colony, the head of the regime department, the head of the operational department, the officers who released me from the colony, took all the papers I had, all the correspondence, those letters that initially reached me, and then stopped. But I tried to save what reached me in 2021, 2022 before the war started, because once the war began, we effectively found ourselves in informational isolation; there were very few letters. Throughout 2025, I received only one letter from my wife, for example. And she didn't receive a single letter from me. It was complete isolation. Besides, I wrote three hundred pages of memoirs about the Maksim Bahdanovich Museum and kept a diary in which I tried to record the conditions so that something would remain. But all of this remained there and was effectively destroyed. They did not allow me to take a single piece of paper out of the colony. This is their attitude towards you; so much for being a Nobel laureate. You are nobody to them there, not a Nobel laureate. Although, knowing what circles other prisoners went through, who were beaten, who were in worse conditions than me, I must say that I was spared that.

— Can you say whether there was torture, inhumane treatment of you?

— Inhumane treatment, definitely yes. As for torture – no. If they lock you in a punitive isolation cell (SHYZA), and you're wearing only light clothing, and the cell is plus 8 degrees Celsius, and you have to sit there for 10 days, unable to sleep because you're shaking from the cold – what is that? That is inhumane treatment. If you can't sit down because the bunks are pinned up, you have to walk, and the bench is narrow – 20 centimeters. This is the place where you can sit at plus 8 in the cell, maximum plus 10, and you're in a shirt – what is that? This applies to all prisoners, not just political ones. This dog-eat-dog Soviet system, which was aimed at destroying any prisoners, smoothly transitioned into the Belarusian system in places like punitive isolation cells, BURs (barracks of reinforced regime, a Soviet-era name. — RS), the colonies themselves, and it smoothly extended to political prisoners, sometimes with a special emphasis, special excesses. Even now, before leaving prison, some political prisoners were held in BURs.

— Ales, how did you find out about Russia's attack on Ukraine in 2022? Did you know that the invasion was also taking place from the territory of Belarus, that Belarus was involved?

— We were in the pre-trial detention center then, and our cell had a TV. We, of course, watched everything that unfolded before the war began, and already from the atmosphere itself, from the information provided by Russian propagandists in programs like "60 Minutes," it was clear that war was inevitably approaching. For me, this became clear about a month and a half before the war, from the beginning of 2022. There were the Olympics, which slightly postponed the start of the war; there were appeals to Putin – don't start until the Olympics are over. Once it ended, military actions began. All of this was dramatically – very, and tragically – very. It was clear that there was a very aggressive attempt to revive the Russian empire, which I had spoken about dozens of times before, recalling the Georgian war, Transnistria, and the very narrowing of the democratic field, democratic opportunities for political parties, public organizations to work. This had been happening year after year in Russia. So when the war started, it was terrifying and tragic. I understood that it would profoundly affect our fate. But what could we do there? Only watch and try to get, extract at least some information, listening, reading between the lines. Both Belarusian and Russian news – they presented it from their point of view. Information that Russian troops crossed the Belarusian border appeared in the Russian program "60 Minutes" almost immediately; they showed these frames – how tanks passed through Belarusian border crossings into Ukrainian territory, and someone from the Belarusian border guards or customs officers was filming these tanks.

Ales Bialiatski in a car the day after his release. Vilnius, December 14, 2025

Then information about missile strikes from Belarusian territory appeared. Then came Lukashenka's incomprehensible and unjustified explanations, claiming that we, they say, were defending ourselves this way because they wanted to strike us, that it was our preemptive strike – some kind of nonsense. It became clear that we were getting more and more involved in this. I thought with great concern and alarm that, God forbid, Belarus would be broadly drawn in, if the Belarusian army were forced to participate in these events. Considering that partly both Zhytomyr and Kyiv regions were occupied, the involvement of Belarusians would be a terrible tragedy, because military conflicts, wars, are not healed and not forgotten by people. We know how well Ukrainians treated Belarusians for all decades before the war. But when war begins, aggression from Belarus against Ukraine, healing these scars will be impossible for decades. They are present even now, but they could have been very terrible – what remains after war for decades.

I think that to some extent this also stopped Lukashenka – apart from the fact that he perfectly understood that then the south of Belarus would also be attacked, and the oil refinery in Mozyr, and the factories in Brest would burn. Here, an economic factor also played its role, because they sometimes think about political consequences last. But the danger of Belarus's full involvement in a full-scale war, aggression, was present for several years. Only in recent months did Lukashenka begin to sing a different tune: that we are a peaceful country, that we want peace. This gives hope that until the end of this terrible war, Belarus will not be a full-scale participant in it.

— Ales, did you notice that most of the Belarusian political prisoners released on December 13 were taken to Ukraine and transported in buses used for prisoner exchanges?

— When we discussed this among ourselves there (although it was forbidden, political prisoners found ways to maintain contact with each other), it was very often said that we were prisoners. We are prisoners during our stay in the colony – considering that in Belarus all these years there has been and continues to be an undeclared state of war. We found ourselves in the role of prisoners against our will, not formally recognized, but nonetheless. That is why all these procedures of our release very often resemble the release of prisoners of war. And how they drove me from the colony with my eyes blindfolded, when I couldn't even tell where they were taking me from Horki – whether to Russia, which is nearby, or somewhere else? I could only guess where we were going. All these nuances show that, in a certain sense, political prisoners who are currently in Belarusian prisons, and there are still over 1000 people sitting there, and new arrests are constantly taking place, some are released, others are recruited – all are effectively prisoners of this regime. We were not ordinary prisoners; we were in a situation of complete lawlessness.

— In Ukraine, there was a discussion in which some released Belarusian political prisoners could not unequivocally say who attacked, who was the aggressor. Was it clear to you there, in the colony, who was responsible for this war?

— It's difficult for me to speak for other political prisoners, because they are very diverse people, a very wide spectrum. Sometimes these are very simple people who do not have higher education, political experience; for many, participation in the mass protests we had in 2020-21 was their first political experience at all. I don't undertake to judge or evaluate, but as for the prisoners with whom I had contact, we all, of course, understood everything perfectly – who the aggressor is, and in what situation Ukraine finds itself, and why it was important for Lukashenka that Russia defeat Ukraine, so that there would be a Soviet Mordor again. Because he was afraid, as Putin is afraid, of the example of a positive democratic transformation of a neighboring country, which could become an infectious model for Russia and for Belarus. They are terribly afraid of this. Just as in the 18th century, Prussia, Russia, and Austria divided the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the reasons was (Catherine II wrote about it) that we, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, including Belarusians, are a hotbed of democratic contagion; we don't need this. This aggression of the 18th century has effectively repeated itself now – that's why Lukashenka participated in it. Because to preserve the totalitarian, post-Soviet system, they need to expand its field.

And for us, for the democratic part of Belarusian society, it is extremely important for Ukraine to remain an independent state, a democratic state, a state – a member of the European Union. Then we too will have prospects of breaking free from this Russian empire, preserving our independence, and ultimately becoming part of the European community. Repressions in Belarus continue, and the situation is now much worse than it ever was – both legislatively and militarily, and nuclear weapons, and the change of the so-called Constitution, when Belarus did not become a neutral state – everything is aimed at preserving the existing power in Belarus, the system of power, the framework of this post-Soviet system. But this is built on sand, on a shaky foundation, because there is a completely different example next door. Next door will be an independent Ukraine, a member of the European Union, if Ukrainians achieve, and I believe in this, the goals and objectives that currently face Ukrainian society.

Ales Bialiatski the day after his release from prison. Vilnius, December 14, 2025

Imagine: Belarus will be surrounded on all sides by EU countries. This is a completely different situation, even compared to before 2020. This is why the aggressors started this war. I'm not even saying "Ukraine – a NATO member"; that's a question mark, a separate issue. The influence of the European Union will be there, and although the authorities of Belarus try to stop this influence, it will be insurmountable. For us, it is strategically important that Ukraine wins this war, strategically wins. It's difficult, with territorial losses, but strategically they are winning, because Putin is not achieving his goals. And his goal is to destroy this country.

How not to understand this, when giving comments like "what kind of war is this," "who will win" – I don't know how to understand it. It means people are not doing any analysis. In prison, information is limited, but you watch Russian television, you see some facts that are happening there, and from these facts, discarding the comments, you can draw your own conclusions about what is happening, that's all.

— Ales, you have assessed the degradation of Belarus's penitentiary and judicial system over these years. How do you generally assess how Belarus has changed since the beginning of the war?

— I have already said that we have returned to Stalinist rails. The only good thing that remains now, undoubtedly, is the people. Absolutely. Despite the fact that I was in prison, I felt morally very comfortable, because the Belarusian people, whatever they may be – they are the same in prison, and the same at liberty, and you sit there among Belarusians. I felt very great and did not experience any discomfort, there was no nostalgia.

There was sadness for freedom, for loved ones. There was an understanding that this regime is not ending, not losing, that it is strengthening and trying to fortify its forces and capabilities at the societal level, at the level of control over society. They did this and are doing it now as a clear minority, simply like a band of terrorists who have seized a train, a city, or a village and are imposing their own order there. But these are not their people. The people are ours, that's what needs to be understood. Our people remain; those who participated in mass protests have not disappeared, although some of them are now afraid to speak out, some have left, some are silent, but the Belarusian authorities now live in a hostile environment. No matter what they show, no matter what they say. That's why I felt normal there.

Ales Bialiatski uses shoelaces instead of laces at a shopping center in Vilnius a day after his release. He was arrested, convicted, and released from prison in these sneakers. Vilnius, December 14, 2025

I take into account that the authorities are not going to give up; they have resorted to unprecedented, unheard-of repressions – we have never experienced such a level of repression as that which befell Belarusian society starting from 2020. This is such a dark period of our history, but it is also a period of struggle. The struggle for democracy, for human rights, for a dignified existence, for justice, ultimately, continues. These are things that simply cannot be eradicated from people. Young people, especially, live on these foundations; the older generation, brought up still in the Soviet Union, is gradually departing; physically, there are fewer and fewer such people. So I am convinced that sooner or later, the situation will change for the better.

It will just be somewhat different from what was planned in 2020, when people peacefully persuaded the Belarusian authorities to start large-scale democratic reforms in the country. No one said, "we will kill you there, we will hang you on poles, you are this and that." They asked, demanded: start reforms. The authorities said "no," responding with repressions that fell upon Belarusian society. This means that the period of confrontation will continue, but eventually, I think, the prospects for totalitarian, undemocratic power in Belarus are hopeless.

— In your words, I hear optimism.

— Certainly, this difficult history, these difficult years we have lived through – 200 years since Belarus was occupied by the Russian Empire – they show that this aspiration for freedom, for independence, is simply inextinguishable in Belarusians.

— Did you help other people in prison as a human rights defender?

— Opportunities there are very limited; what could I do there of what I did when free? Nothing. Of course, we shared when we received any parcels; there was an opportunity to help each other, primarily political prisoners. But this did not concern only them. Many prisoners helped me: it could be a chocolate bar, simply a kind word, the assurance that this person would not metaphorically throw a stone at your back. That you could sleep peacefully, not worry about your life. This solidarity of people who were in prison, political ones first and foremost, was very strongly felt. I was in the same condition as everyone else; when I received, I naturally shared, gave away cigarettes, and some of the most basic things. Nevertheless, I never lost the thought that our stay in prison is our human rights work.

— What would be your message to those who are still in prison, to political prisoners, to those who are free but in emigration, to those Belarusians who are at home waiting for better times?

— Do not lose hope, do not give up, continue to work for yourselves first and foremost, for Belarusian society, for an independent democratic Belarus.

Now reading

Ihar Losik recounted how he was held in the KGB pre-trial detention center with a former delegate of the All-Belarusian People's Assembly — a police colonel who, while drunk, almost killed his wife

Comments

Спадар Алесь, найхутчэй Вам акрыяць пасля вязніцы, а там і Вясна не за гарой.